Molly Crusen Bishop: Woodruff got things done despite controversy

- Details

- Published on Monday, 07 December 2015 18:13

- Written by Molly Crusen Bishop

Editor’s note: E.N. Woodruff was one of Peoria’s best known mayors during the last century. Columnist Molly Crusen Bishop used various sources to piece together this biography so our readers could get to know him better.

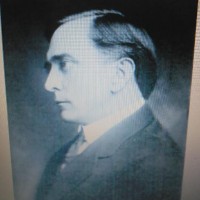

Edward Nelson Woodruff was born Feb. 2, 1863 to Peoria city pioneers Nelson Lot Woodruff and Mary Ann Monroe Woodruff in their home at the corner of Pecan and Washington Streets in Peoria. He was one of seven children.

His father was a New York native who moved to Ohio and then to Illinois at the age of 17, when he led a team of horses to this state and settled on the edge of Kickapoo Creek in 1835 near Peoria, which had a population of less than two thousand at the time.

Nelson built the first canal boat used on the Illinois River that went between Peoria and Chicago and later operated a riverboat called “Fort Clark” until 1855. He later formed the successful Woodruff Ice Co. Nelson built the fasmily’s second home in 1876 on North Jefferson Street to be near the ice plant, which was near the river.

Nelson Woodruff died in 1879, changing the course of Edward’s life. After Nelson’s death his widow Mary, a native of Pennsylvania, was made president of the ice company and Edward left Peoria High School to begin running the day-to-day operations of the company. He became company president after his mother died in 1890.

Edward grew up watching the workers cut the ice on the Illinois River with their long saws each winter, getting the company’s supply of ice. He learned the business well and saw how they preserved the giant blocks of ice in straw to be stored in the ice houses. He rode the ice wagon daily from home to home and delivered ice in every part of Peoria.

The ice trade during the late 1800s involved large-scale harvesting, transporting, and selling of natural ice for domestic and commercial purposes. It was sold in such large amounts in this time period in the United States that it made the cost significantly lower. The ice supplies instantly dwindled and Woodruff used his daily deliveries and collections to educate Peorians on being ice-conscious and how to conserve their ice.

E.N., as Edward was also known, enjoyed the daily deliveries and interactions with people. He was intrigued by people from all walks of life. While making deliveries and collections he would have conversations, discussing both happy topics and listening to their troubles. He was a great listener and literally met thousands upon thousands of regular folks who became friends and connections. He was laying the foundation upon which his future lengthy political career would be built.

This foundation later became known as the “Woodruff Machine,” which kept him in power for decades.

It started around the turn of the century when Peoria needed a Republican nominee for First Ward alderman. A search for a familiar face to clinch the seat led to one who was both kind and well-known. The man who had delivered ice to both the poor and the rich came to mind and E.N. Woodruff the seat by a majority of 479 votes.

E.N. had always followed city affairs and was filled with energy and excitement. He won a second term as alderman and was highly popular. E.N. became known as a champion of the people by boisterously arguing for or against causes he believed would help the people of Peoria. By then he was married to Anna Schmidt and they had one daughter, Mary Woodruff. He built a home across the street from his parent’s North Jefferson Street home in the early 1900s.

E.N. won his first mayoral race in 1903 and succeeded Mayor William F. Bryan. His campaign would run on a promise that he wanted the people of Peoria to get 100 cents for every dollar they paid into Peoria’s treasure; he was quite successful keeping this promise. He oversaw extensive public improvements during his tenures as mayor of Peoria. The garbage department, health department, and the sanitary sewer systems were established as well as several Illinois River bridges, including the first free bridge. Other improvements were sidewalks, roads, and masses of city services. He was able to accomplish all of this without heavily taxing the average folks in Peoria.

How did E.N. manage to do this without heavy taxes? With a lot of controversy.

E.N. Woodruff believed that all cities would have vices and he had an attitude of keeping his city wide open. He figured the vices would happen regardless of the law, so he may as well get services for the citizens of Peoria out of it. So, he basically allowed brothels, gambling, and alcohol (during prohibition) joints to pay fees or fines into a fund he called the “Madison Avenue Fund” (City Hall was on Madison), which had enough money to build the infrastructure of a city the size of Peoria well.

He was never accused of “being on the take” for his personal accounts. There were gambling joints spread all over downtown Peoria as well as three red light districts for more than 77 brothels in the city. The Shelton gang literally moved their headquarters from East Saint Louis to Peoria during Woodruff’s reign, leaving the door open for more underworld characters to come from Chicago and all around.

E.N. was a charismatic man who could smooth over almost any disagreement and was knowledgeable in many diverse topics of business as well as pleasures. He ran for mayor of Peoria an astounding 18 times. He won 11 of these campaigns, serving mostly non-consecutive terms between the years of 1903-1945. In the early part of the century, a term lasted only one year, so he was almost constantly campaigning.

One of his many nicknames was affectionately “Little Napoleon” for his ability to be continually voted out of office only to later reemerge as the mayor again years later.

Starting around the year 1910 he did serve for almost a decade straight, with several successful dealings that brought him national attention. He and the State’s Attorney at the time, C. E. McNemar, were able to restore order after rioting at the Keystone Steel and Wire Co. that was spreading terror throughout the city. In 1919 the workers at Keystone were on strike and the company was bringing in strikebreakers. The strikers placed logs on roads and shot at the company owners who were trying to sneak the strikebreakers into the plant to work. The owners of the company were even spraying firehoses at the strikers to distract them. Some of the strikers were hiding on the side of the road with guns and several people were shot and hospitalized.

This was becoming a city-wide problem and Woodruff and the state’s attorney requested the state send in National Guard troops for help. More than 2,900 troops were sent to quell the strike, but the strike ended peacefully, to Woodruff’s credit, when those troops began arriving by train.

Woodruff had run-ins with strikers even before that. In 1912, the I. W. W. (Industrial Workers of the World) went on strike at Avery Implements in Peoria. What were described as “IWW gunmen” came in and wreaked havoc. When they were arrested, bondsmen would get them released within minutes and then violence would abound. So, Woodruff had the gunmen and the bondsmen placed in jail on a mass conspiracy warrant and he told them to leave the city or stay in jail; they left Peoria.

Edward Nelson Woodruff was a machine politician and he controversially shaped Peoria’s infrastructure, culture, business, and underworld for well over 40 years. He ran his political headquarters on his property along the Illinois River north of Peoria near Rome on a beached riverboat cottage that was affectionately called the “Bum Boat.” His administrations were full of scandals and yet he had an excellent record for city improvements that managed to get him re-elected 11 times in his 18 runs for mayor of Peoria.

However, by the 1940s Peoria became known as “Roaring Peoria” and city services were declining. Corruption, organized crime, gambling, prostitution, all led to a decline in the city of Peoria and ultimately led to the end of his career in the mid-1940s, when he lost the election to a reformer named Carl O. Triebel.

Edward Nelson Woodruff died Dec. 22, 1947. He was 84.

He was mayor a total of 24 years and during the decades he was involved the population of our river city grew to more than 100,000. He was nationally known; he was once invited to a memorial by President Herbert Hoover to honor Abraham Lincoln.

Peoria was plagued by gambling, prostitution, and alcohol and suffered the usual symptoms that come from these issues, yet E.N. was a popular man who could talk and walk with the regular folks from his days on the ice wagon. He was a Mason, a Shriner, an Elk, a Modern Woodmen of America, a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. He brought the garbage, health, sanitary sewer departments to life, as well as bridges and Eckwood Park, had a high school named after him, helped build the First National Bank Building and the Hotel Pere Marquette.

He was a controversial, yet much-loved man who shaped Peoria into what it is today.