Frankly, The Origins of Saving Daylight Goes Way Back

In 1918, several months before the steamboat Columbia sank in the Illinois River, Daylight Saving Time was enacted in the U.S for the first time. Here is an excerpt from my book, “The Wreck of the Columbia: A Broken Boat, A Town’s Sorrow & the End of the Steamboat Era on the Illinois River,” Chapter 19 – DST.

It was late on March 31, 1918, a Saturday night soon to be a Sunday morning and the beginning of a new month, when Daylight Saving Time officially became a household phrase in America. It started with a crowd of gawkers lining the streets surrounding the Metropolitan Building in Manhattan. At exactly midnight, the crowd strained their necks and looked up at the huge lighted clocks, each 26 feet in diameter, one on each side of the building. A signal was given and the lights shut down—the largest four-dial clock tower in the world went dark.

A hush came over the crowd.

Time was literally at a standstill.

Then there was a cheer!

The crowd was festive despite the late hour and the start of Easter Sunday. A community chorus sang the “Star Spangled Banner,” and the New York Police band and Borough of Manhattan bands took turns playing “Over There.” The excited throng kept staring at the clock dials frozen in time. It just couldn’t be, they thought.

It was deep in the tower’s belly where all the work was taking place. Hired mechanics had made their way up to the tower’s inner workings and begun the arduous task of advancing the 13-foot hour hands manually. They had two hours to get the job done. Then promptly at 2 a.m., the lights flickered on again. Like magic, the clock tower was once again illuminated. Hundreds of late-night souls strained their necks again to see the clock dials’ hour hands in the glowing beams. The hands were pointing to the number … 3.

Three! It was 3 o’clock! For the first time in history, the nation had moved itself ahead one hour. The crowd shouted and cheered. Daylight Saving Time had officially begun.

“Blasé New Yorkers for whom New Year’s Eve celebrations have lost their thrill,” wrote a reporter for the New York Times, “rubbed their eyes and marveled at the novelty of an Easter Sunday of only twenty-three hours.”

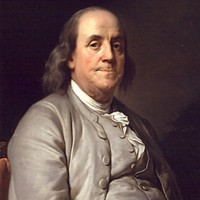

The idea for daylight saving is most often attributed to Benjamin Franklin during his years as an American delegate in Paris in the late 1700s. Thanks to the oil lamp, Franklin would stay up late, usually playing chess, and sleep until noon the next day. One morning, quite early, he was awakened by a sudden noise. He threw open the tight window shutters and was even more startled by the amount of daylight coming into his room. “I looked at my watch,” Franklin later wrote in an article that appeared in the Journal De Paris on April 26, 1784, “which goes very well, and found that it was but six o’clock; and still thinking it something extraordinary that the sun should rise so early. I looked at the almanac, where I found it to be the hour given for his rising on the day.” Perhaps with a mix of astonishment and dry humor, Franklin wrote “that having repeated this observation the three following mornings, I found precisely the same result.”

Ever resourceful, Franklin had an intriguing thought. If he had slept six hours until noon through daylight and “lived” six hours the night before in candlelight, then wasn’t that just a waste of precious light and expense? “This event has given rise in my mind to several serious and important reflections,” he wrote. Franklin went to work figuring out the math. Assuming that 100,000 Parisians burned half a pound of candles per hour for an average of seven hours a day, and calculating the average time during summer months between dusk and the time Parisians went to bed, Franklin concluded that the amount saved, as he put it, would be an “immense sum.” Franklin proposed that all Parisians rise with him, when the sun rises, and to compel the naysayers, he proposed “a tax [be laid] per window, on every window that is provided with shutters to keep the light out.”

“Let guards posted after sunset to stop all the coaches that would pass the streets,” he bravely declared. “Let the church bells ring every time the sun rises. Let cannon(s) be fired in every street, to wake the sluggards effectually, and make them open their eyes to see their true interest.”

Franklin’s dry wit and humor notwithstanding, his scheme alarmed Parisians who weren’t ready for change. They thought Franklin’s idea was madness, and a surprising one at that, coming from an American intellectual and a figure that was so well-liked in France. After he left Paris, Franklin mulled over the idea and marveled at “inhabitants,” this time Londoners, who continued “to live much by candlelight and sleep by sunshine.” Franklin used the economy as an example, saying residents had little regard to the costs of candlewax and tallow. “For I love economy exceedingly,” he explained.

Eventually the idea of extending the day during the summer months was proposed. Instead of getting up by daylight, usually too early, then why not just move daylight later in the day and prolong the evening sun?

"Everyone appreciates the long, light evenings,” wrote William Willett, a London Builder who is credited with the idea of extending daylight. “Everyone laments their shortage as Autumn approaches; and everyone has given utterance to regret that the clear, bright light of an early morning during Spring and Summer months is so seldom seen or used."

Like Franklin, Willett was struck by the amount of people who kept their blinds shut in the morning hours even though the sun was fully out. If getting up too earlier was the crutch, thought Willett, then why not just stretch the light of the evening hours. European countries would adopt the idea first.

On April 1, Easter Sunday of 1918, Americans did as well.

Excerpt from The Wreck of the Columbia: A Broken Boat, a Town’s Sorrow & the End of the Steamboat Era on the Illinois River © 2012 by Ken Zurski. Used with permission from Amika Press.